|

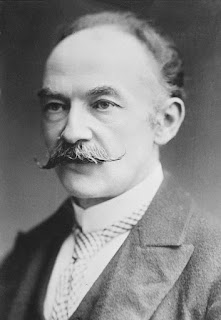

| Thomas Hardy: born 2nd June 1840 died 11th January 1928 |

This novel, published in 1891, resonates, in surprising but subtle ways throughout our own social strata. Indeed, the central theme of this work, viewed by many as Hardy’s masterpiece, hinges upon the importance of female virginity before marriage.

This consideration was reflected as recently as the 1981 marriage between heir to the British throne Prince Charles and Lady Diana Spencer. Despite their twelve-year age difference, and their vastly diverging interests, Lady Diana’s virginity rendered her one of the limited number of candidates acceptable as Princess of Wales, and potential mother to the next king of Great Britain.

From its beginning, Tess of the d'Urbervilles is based upon a false supposition. During a time of major economic depression in the 1870s, Tess Durbeyfield's father becomes absorbed by a hint from his vicar of his possible connection to the similar named family the "d'Urbervilles", who possessed significant wealth.

Without any further verification, Durbeyfield determines to seek to gain whatever he can from this tangential connection. Hence, after correspondence, Durbeyfield invests the family’s meager financial resources in sending his lovely, seventeen-year-old daughter, Tess, to visit their “relatives”.

Once having met her, Alec d’Urberville, accustomed to obtaining whatever or whomever he fancies, soon grows amazed by Tess’s ability to resist his amorous efforts. Slowly, unused to the slightest rebuff, his feelings increase, until they begin edging towards love.

As to Tess, while she does her utmost to avoid becoming one more in a series of discarded conquests, she begins to pulsate. In theory, she remains on the d’Urberville estate in hopes of her small wages as poultry keeper will compensate her family for its outlay regarding her journey. Later, during a night in a field, her intimacy with d’Urberville is crystallized.

Hardy leaves it to the reader to determine to what degree, if any, her response is consensual. During the late Victorian era, the thought of a girl or woman, especially if unmarried, feeling lust and or libido, could not be endured. Thus, in this and other novels written by authors during the same era, the writer and reader collude in a form of political /moral correctness.

At any rate, this encounter results in Tess, humiliated and pregnant, returning to her village. Although her baby lives only a few weeks, its conception and birth has made her a pariah. Any hopes she might have of respect lies in traveling some distance.

Having found work on a dairy farm, she encounters the apprentice minister, perhaps satirically named Angel Clare. Despite his bountiful choices as to a bride, Tess’s beauty and integrity urges him to propose. Tess, having become besotted by Angel, fears confession of her indiscretion will impel him to retract his proposal. (in the most ominous sense, she is right.)

Hence, although Tess and Angel marry, anguish soon besets them.

On their wedding night, Angel admits to a brief but wild interlude with an older woman. Engulfed by a sense of relief, Tess reveals her encounter with Alec d'Urberville. Angel, appalled and overwhelmed, explains to Tess her seeming innocence had induced him to ask her to become his wife; her words have flawed his belief in her to the point of his inability to consummate their union. After several days of strain, Tess urges Angel to leave. He agrees, promising to strive, from his deepest soul, to find some means of forgiving her.

The remainder of the book involves plot twists too intricate for our purposes here. To summarize, Alec d’Urberville, finding Tess and her family near destitution, offers to support all of them if Tess will live as his mistress. She agrees, again ostensibly based on need rather than any erotic wish.

While acknowledging Hardy’s genius, some critics have noted his tendency to force his characters to commit acts almost wholly inconsistent with their previous conduct, in order to facilitate the conclusion he seeks. While I will not ruin the ending for future readers, I join with those who maintain Tess’s subsequent actions fall into this somewhat puppeteer pattern.